I found out my cousin died, on FB, or other weird ways to announce death.

How is the next generation of Igbo people handling the intersection of tradition and technology? “But you ought to ask why the drum has not beaten to tell Umuofia of his death.”- Achebe

“You have to come with your elders. You can’t just come alone and just come and announce that, oh, we lost this thing. You can’t just outrightly go and tell them, oh, we have lost your daughter. No, it’s not possible. Like, you come home, they’ll see you, talk to you normally, offer you this thing. You go, come, you come back again, maybe at your third meeting, they will not ask you, “okay, what truly is bringing you here?”.”

- Amaka, ‘Onwu Sure For You, a Millennials guide to Death’

I don’t think I’d ever felt the pregame to receiving bad news until the time I received one that my paternal grandfather had died. It was 1996 and I was called into my father’s bedroom suite. My father was sitting on his blue-grey massage chair that up until then had been a source of endless joy and play for me. Whether because I snuck into his room, sitting in it while pressing the various buttons, popping out the leg rest up and down, or I was invited in, sitting on the leg stool facing my father and biting into a shared platter of isi ewu, nkwọbi, roasted bush meat, stewed snails or spicy suya, whichever my father desired as his late-night snack of the day.

This time I walked in and the room felt warm. The AC in my father’s room typically kept the room so cold, my teeth chattered at times, but that day I wondered if it was defunct. The cold instead seemed to come

from somewhere inside me. My father was in a silhouette that I had never seen before. His head was leaned back against the chair’s neck rest, his eyes looking up to the ceiling and he was quiet. Still.

I ran through possibilities of bad news: an imminent estate system breakdown, a Nigerian government coup, the super eagles losing a match, or an even more delayed shipping containers of goods for his business. Still, none of these previous scenarios had presented my father in this way. Subdued. Without words. Unable to look at me directly in the eyes.

I stood waiting until my father finally leaned forward in the chair, his head down. I then noticed his bedroom cordless phone in his laps as he finally looked up at me and said “Your grandfather has died.”

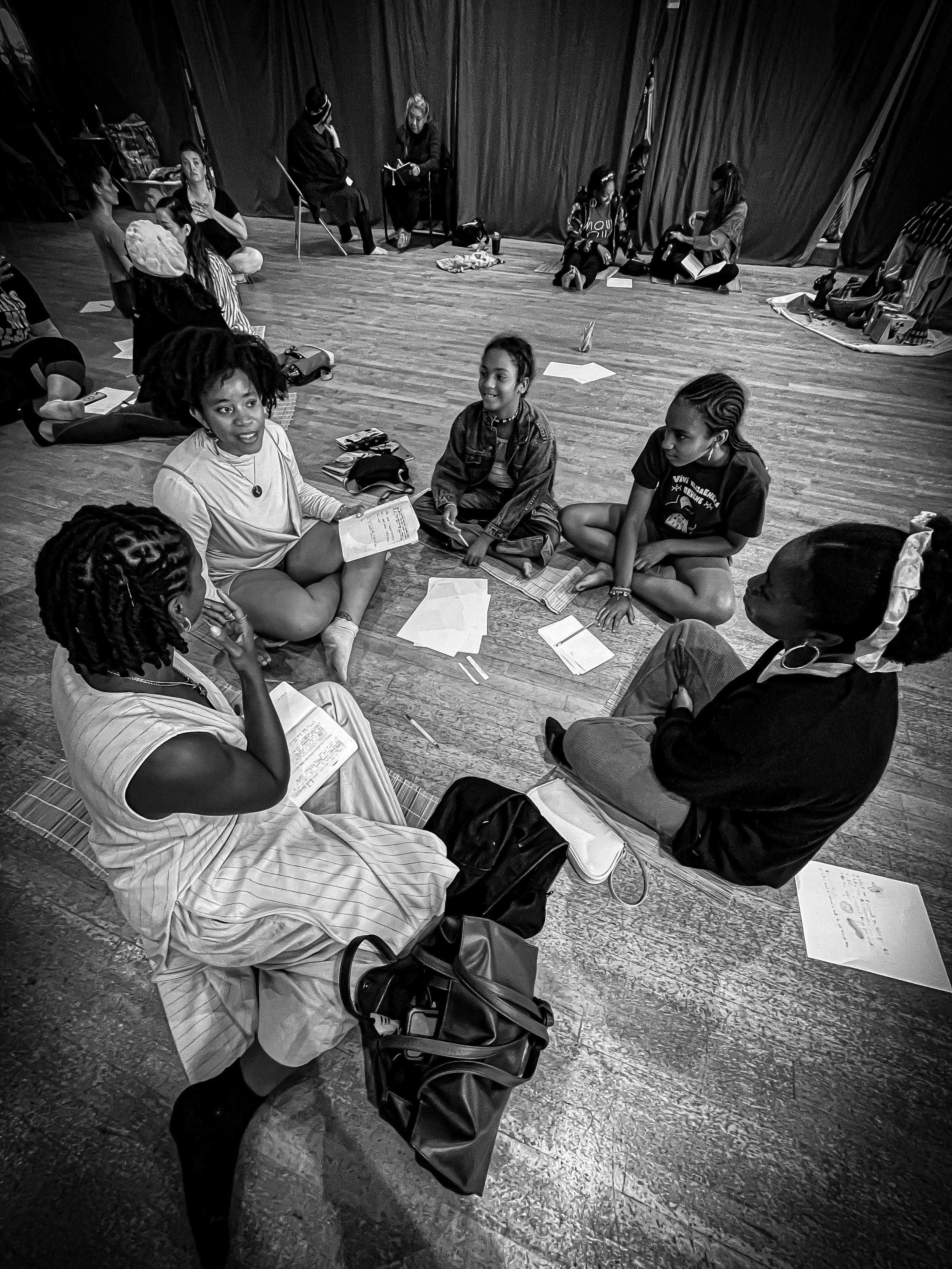

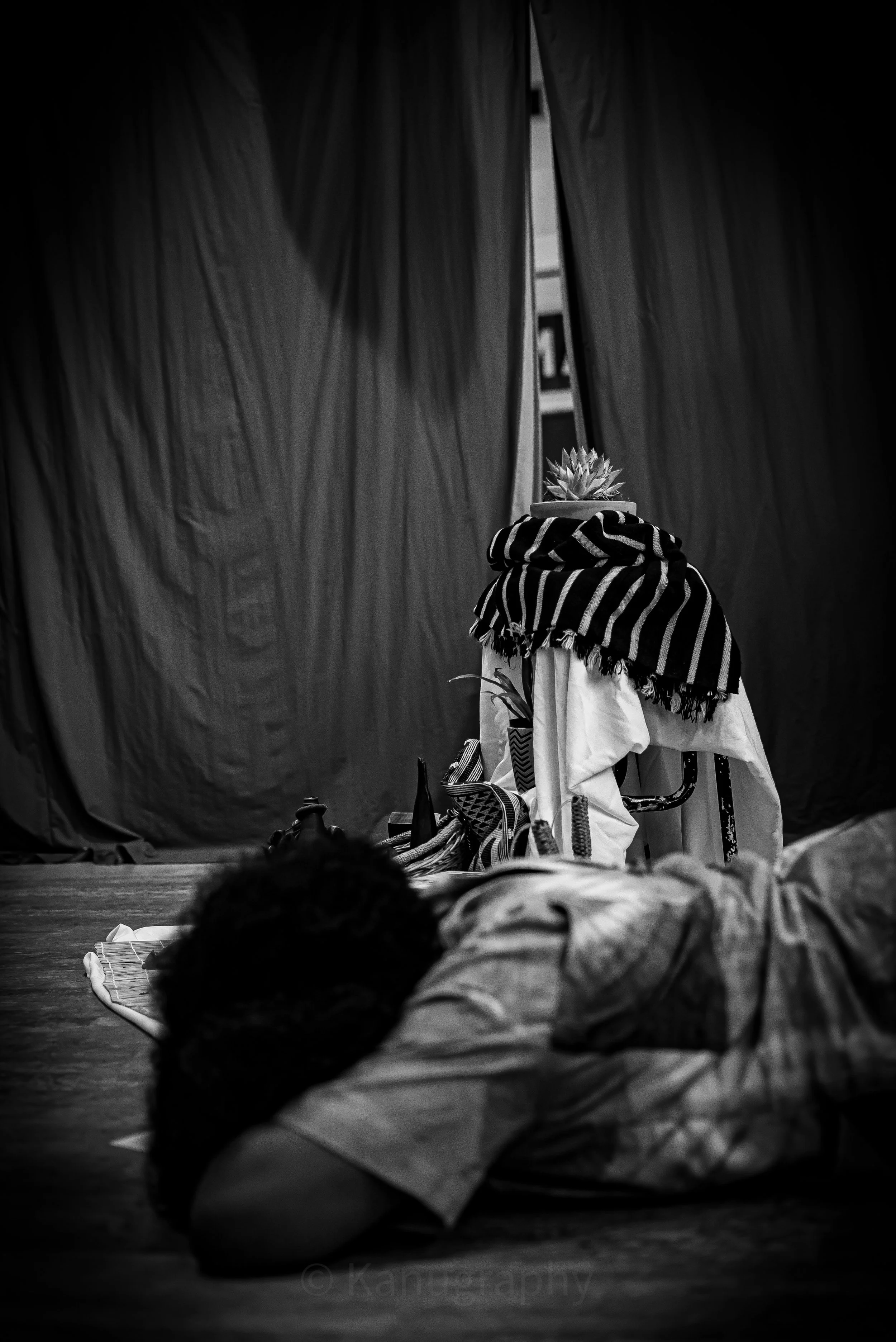

Receiving news and sitting with it. Photo by S.BdeM

Traditionally, in many Igbo societies, death is treated with a very prescribed and intentional set of norms and rituals. And how you announce death is not exempt. For the last five years I’ve been curious about what these practices are, how different communities facilitate them, and what challenges and opportunities these knowledge systems provide for us now.

I was a child when my father buried his father, and I am now an adult who has since buried her own father. I want to know what, and how the information from our cultures are intentionally passed down to us, the next generation. So I’ve been talking to elders, and adults of the present generation about their experience, creating multimedia work to share these narratives. A documentary in the works has me focusing on millennials who have experienced the death of a parent and how they navigated.

One of the people I interviewed, Amaka, shared her experience with both her father and mothers deaths, and I was really fascinated with the protocol she described in how you announce the death of a loved one formally to their family and the community.

“You have to come with your elders. You can’t just come alone and just come and announce that, oh, we lost this thing. You can’t just outrightly go and tell them, oh, we have lost your daughter. No, it’s not possible. Like, you come home, they’ll see you, talk to you normally, offer you this thing. You go, come, you come back again, maybe at your third meeting, they will not ask you, “okay, what truly is bringing you here?”.” - Amaka, ‘Onwu Sure For You, a Millennials guide to Death’

In the past seven years, I’ve experienced an unending stream of loved ones dying, and the impact has run the gamut from incessant wonder, lost sleep to a stalled and debilitating couple of years. From my father’s, to very close family, friends, community members, there’s been a variety of ways that I’ve received and delivered the news. My sister and I have bemoaned the amount of times someone just randomly sends a text, when we felt we should have at least received a phone call.

Or times when we’ve heard about people finding out on social media, because someone opens their big mouth before the family goes through their internal protocol and makes their own announcement.

But like they say ‘Bad news travels fast’, so I guess we just have to accept that it may come in the form it does? I’m not sure how I feel about the way we navigate news telling now. I’d like things to be slower and more intentional. I would want to be around other loved ones. A bit of pregame. But I want to know what others think.

How do you feel about how we navigate death news in our society/families/world today? How are death announcements typically handled in your culture or community? Do you feel like those practices should be modified? What would you like to see more of? Less of? Is a text or social media post the way?